This is despite the fact that, in 2006, with the arrival of the electronic DNI, a digital signature was developed that allows, as was already done with the income statement, certain procedures to be carried out, with the same legal validity as a handwritten signature. Installing this on a PC was not intuitive, and in fact the system remains the same 14 years later, which has undoubtedly been and continues to be an obstacle for a population that, until recently, was still too analogue to deal with security certificates.

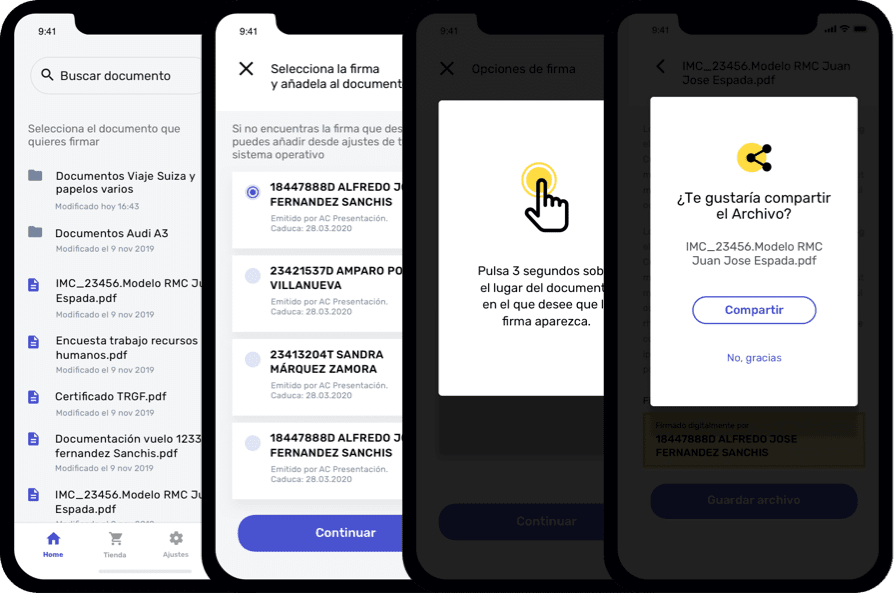

The arrival of the smartphone has accelerated not only the improvement of the digital skills of the average user, but also the simplification of processes, to the point that a legally valid electronic signature on any document, using an app like USign, takes less than 20 seconds. This is a huge time saving, especially for managers with a large volume of signatures to be provided and trips that prevent them from being everywhere they would like, or administration offices who need agility in their day-to-day activities.

The previous example is just one that perfectly illustrates that an analogue administration or company cannot cope with a digital one, simply due to inefficiency. If, therefore, it is not digitised, it will disappear due to lack of competitiveness, which in the case of administration is more urgent, since the lack of competitiveness affects the State as a whole.

“Digital has come to stay and since it changes everything, everything has to be changed.”

Spain is well positioned in the existing indices in the international context in terms of electronic administration and digital transformation. According to the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2020, our country occupies 2nd position in the dimension of digital public services, climbing from 4th place previously, and 11th among the 27 member countries of the EU.

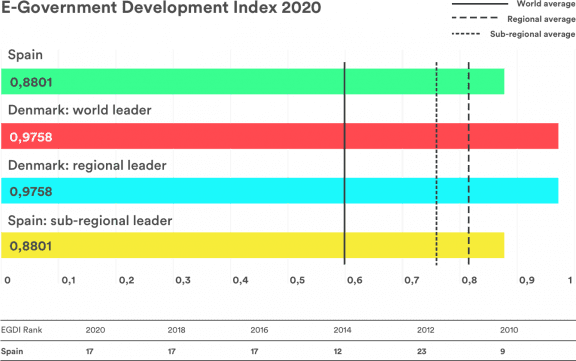

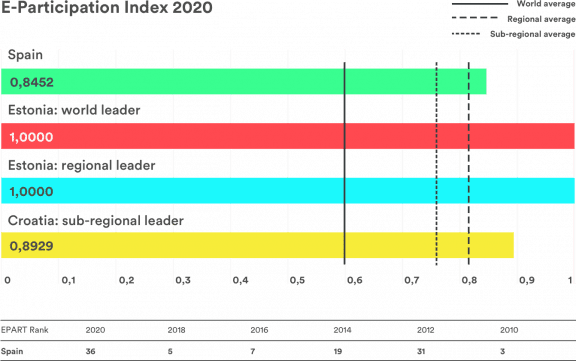

The UN eGovernment Survey 2020 of the United Nations also places us within the leading group on the e-Government Development Index (EGDI), where a total of 193 countries are studied.

Specifically, in the E-Government Development Index, which led by Denmark, we are placed in 17th position, and 36th in the Citizen Participation Index. In 2018 we were in 5th place, meaning we have fallen 31 positions in this section, where Estonia now leads, rising from 38th position in 2018.

To determine the degree of compliance with the aforementioned laws in 2018, Ernst and Young (E&Y) published a report in 2019 on digital administration in Spain. The objective was to consider "the perceptions of a user (citizens and companies) who needs to carry out an online procedure". Specifically, the investigation revealed not only the high delay in administration (currently more than two years), but also the gap between the different administrations (autonomous communities, county councils and town halls). Reading between the lines, the report shows that, despite the fact that there are more and more forums in which officials can share knowledge, collaboration between administrations and institutions, to generalise good practices, still has much room for improvement.

We started this article talking about the ease of signing documents with applications like USign. Well, although this is a perfect application for use between companies and individuals, it would be great if all administration processes were adapted for the use of these tools. The E&Y report reveals that, regarding “Digital identity and electronic signatures, only 23% of communities have achieved 100% of the objectives [of the Laws described], which drops to 9.5% in the case of Spanish town councils.”

Regarding "Assistance to citizens and companies, 59% of the autonomous communities register a favourable result, achieving compliance with all the requirements, compared to 47% of the municipalities and 42% of the councils." This is despite the fact that it is already possible to manage quick and direct access by chatbot, for example, like the one designed for the Castellón Provincial Council.

Nevertheless, the situation is improving and the administration continues to advance with projects such as the Digital Spain Plan 2025, with an ambitious initiative to go from 10% of public services currently available in the form of an app to 50%, as well as updating all the back end of the apps to take them to the hybrid cloud, and thus be able to respond to peak demand.

The plan, however, juxtaposes all the objectives, but does not articulate policies to achieve them intelligently. It is full of terms such as liquid infrastructure, hyperconnectivity, interoperability, artificial intelligence, intelligent digitisation, which although they bring us to the future, do not carry a ticket for the trip.

A new initiative, which is also included in Spain Digital 2025, is the launch of a GobTechLab, one of which already exists in the community of Madrid, in line with the GobTechLab in the United Kingdom, which provides a clue to the usefulness that this laboratory will have, which is oriented to those who are interested in the interface between emerging digital technologies and government. “The purpose of GobTechLab is to facilitate the discussion, adoption and exploration of new digital technologies (AI, Internet of Things, Big Data, Blockchain) in order to support the adoption of these technologies in the public sector.”

“We cannot digitise Spain without modernising the administration.”

What does Estonia have that everyone falls in love with?

Thus, it is not surprising that Estonia now occupies 7th position in the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI), where Spain is positioned 11th. Estonia occupies 1st position in the digital public services dimension of this index, where Spain is 2nd, yet this is not influencing our economy as well as it could, and digitisation by itself is not synonymous with efficiency.

So what does Estonia do differently?

To begin with, its X-Road system, which interconnects the different areas of the administration and has been in place since 2001, guaranteeing Spain to be in the 11th position, that is, the public administration can only request the personal data of a citizen once, which in itself it is already a considerable time saver. After this, only weddings, divorces or the purchase of a real estate require a physical presence, all other procedures are carried out online. A total of 2,773 procedures can be completed through this system.

As such, the tax agency has been converted into a service and it is possible to obtain online information about the status of your company or staff in real time. Perhaps that is why Estonia occupies 1st place in the Ranking of Fiscal Competitiveness Index 2019, carried out by the Tax Foundation and presented in Spain by the Institute of Economic Studies.

Another point in their favour is that they have managed to transform a weakness into a strength, since the Achilles’ heel of a fully digitised state is its cybersecurity. In 2007, Estonia suffered a cyber-attack, which some blame on Russia. Following the incident, in addition to creating an army of cyber volunteers, many of them from leading companies, the context was set for the recognition of Estonia's cyber defence leadership. Six other nations, including Spain, joined forces to establish NATO's Cyber Defence Cooperative Center of Excellence (CCDCOE) in Tallinn.

Aware of the importance of talent, they have sensed how the digital economy works like nothing else. A digital economy is global, so in 2014 the country launched E-Residency, which is a simple digital residence card, which a citizen of any country can request, for example from Latin American countries. Although this does not give the option of residing in Estonia, it does suffice, for example, to set up a company there, and therefore in the European Union.

This card allows the holder to perform any procedure online and from anywhere in the world, such as opening a bank account in Estonia, making online payments, signing documents or paying taxes.

Recognising that there is a growing mobile workforce that is highly qualified and willing to take the opportunity to settle in a country like Estonia for a limited time, has also motivated them to design actions to attract raw material talent in the era of digitisation.

Thus, the administration offers the possibility of knowing, guided by specialists, the best practices of e-Estonia, which will undoubtedly create links with the main IT service providers and state experts to support their digitisation plans. In addition, if they have already offered the possibility of becoming a digital resident, from August 1, 2020, remote workers can apply for a digital nomad visa for reduced stays of up to one year, although with some caveats, for example a fee payable by the applicant of 3,504 euros (without taxes), which in itself pre-selects a very specific applicant profile and is aligned with the search for talent.